By Miles Franklin

The Art Institute brings to light the rich history between Claude Monet and the city of Chicago in a dazzling exhibition.

Miles Franklin / The Chicago Maroon

Claude Monet casts such a grand shadow in the history of European art that the very mention of Impressionism invariably conjures images of Monet’s water lilies, garden scenes, and landscapes before it brings to mind any other artist. In fact, the very term “Impressionism” comes from a Monet work titled, Impressionism, soleil lavant. Impressionism as an art form dominated Europe in the latter decades of the 19th century, and it has found its footing in the 21st century in large part thanks to Monet who, above other equally talented Impressionists such as Pierre-August Renoir, Camille Pissarro, and Paul Cézanne, seems to have captured the imagination of young art enthusiasts. Despite all of the credit due to Monet, one must wonder how he, a fiercely European artist, can be so implicated in the history of Chicago’s art scene that The Art Institute of Chicago would name their current Monet Exhibition Monet and Chicago.

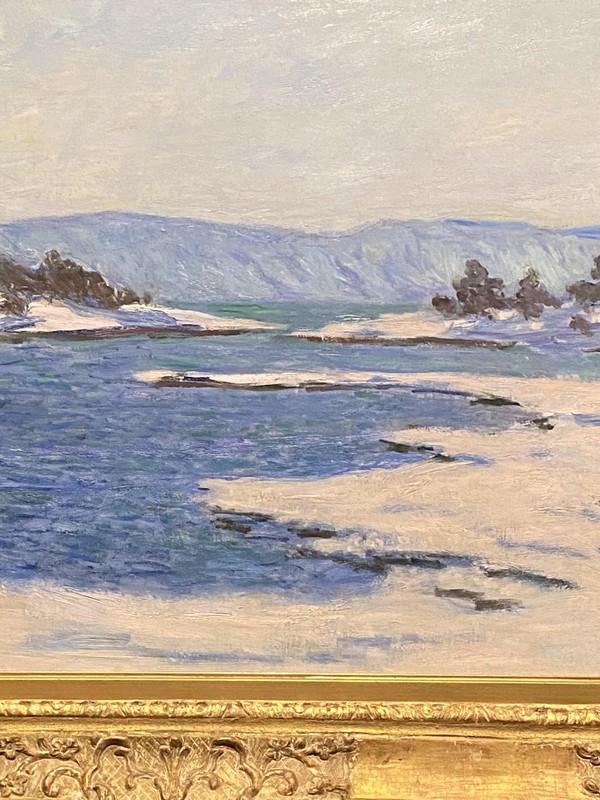

Figure 1 Detail of The Banks of The Fjord at Christiania, 1895.

In actuality, Claude Monet owes much to Chicago and The Art Institute owes much to Monet. This notion is quite curious when one considers that Monet purposely avoided ever traveling to the United States, disliked Americans, and believed that Paris was “the only place where there is still a little taste.” However, French Impressionist artworks landed in Chicago through Thurber’s Art Gallery as early as 1888—among the works on display, Monet’s were noted to be the best. Of this event, an 1888 Chicago Daily Tribune quote that hangs prominently in the new exhibition states, “Why go to Paris when Paris has to come to Chicago?” Perhaps it was this brash American self-importance that kept Monet from ever setting foot in the United States; fortunately, our Americanisms were not enough to keep his paintings out of North America. In 1891, after another showing of Monet’s work in Chicago, prominent local collectors Bertha and Potter Palmer acquired 20 of Monet’s works in a move that would start Chicago’s insatiable appetite for Monet and eventually lead to The Art Institute’s outsized collection of Monet paintings and drawings, the largest in the world outside of Paris. Following the Palmer’s acquisitions, The Art Institute hosted Monet’s first-ever solo show in America in 1895, titled 20 Works by Claude Monet. Later in 1903, The Art Institute became the first American museum to purchase work by Monet which only furthered donations and acquisitions. The mutually beneficial, if partially reluctant, relationship between Claude Monet and Chicago’s art scene is surprisingly profound, and this historical context is not lost on Monet and Chicago.

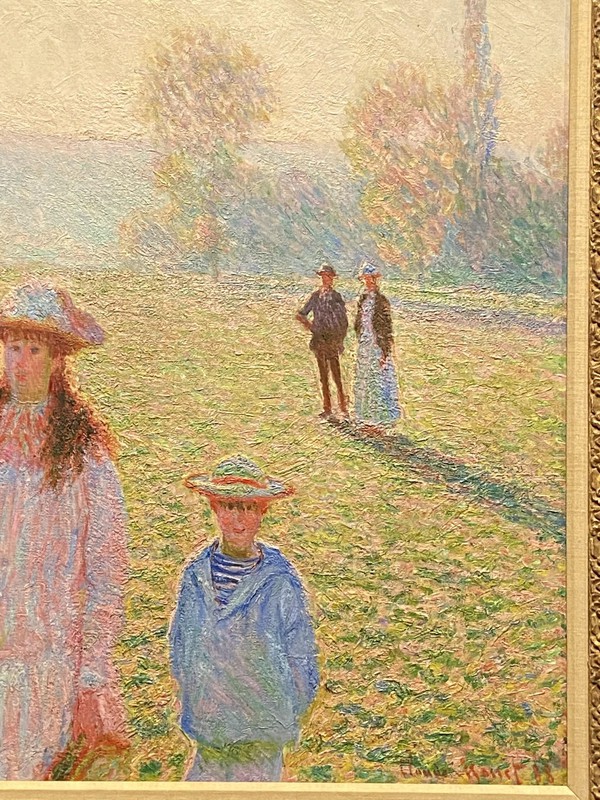

Figure 2 Detail of Landscape With Figures, Giverny, 1888.

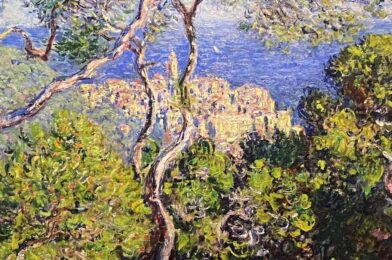

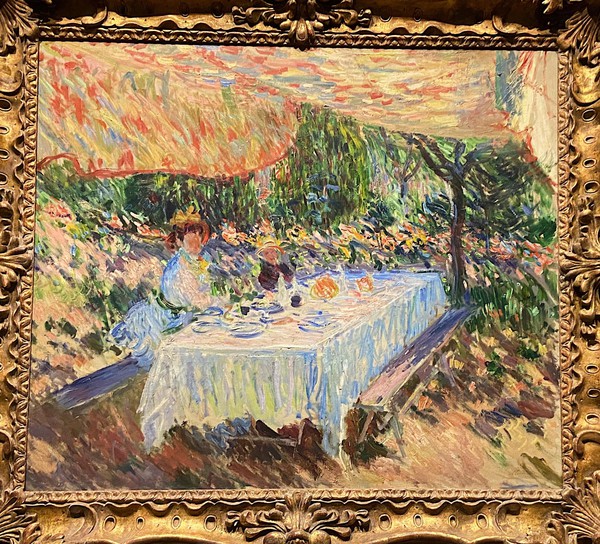

Without giving away too much information, as I think this show must be seen in person to be fully appreciated, I must say that Monet and Chicago is a landmark exhibition. With over 70 paintings and drawings by Monet, spanning some of his most famous series as well as much of his lesser-known work, the exhibit is a true tour de force, and the difficulty in coming by tickets attests to this fact. What is particularly remarkable about this exhibition is the broad sampling of Monet’s subjects and artistic eras, a luxury afforded by the sheer number of works on display. Visitors are charmed into the countryside, streetscapes, and gardens of France, elevated to the sublime in masterful depictions of the Italian Riviera, sunk deep into contemplation in Norwegian snowscapes, and placed in the middle of a train station bustling with life in Paris.

Yet, even as viewers gaze with deep admiration at the layers of seemingly haphazard brushstrokes that define the works of Monet and many other Impressionists, the tumultuous nature of Monet’s personal life cannot be ignored.

Figure 3 Water Lily Pond, 1900.

Literature such as A Day With Claude Monet in Giverny by Adrien Goetz suggests that Monet exhibited manipulative tendencies towards his children and his wives, viewing them more as accessories to his life and less as autonomous human beings, but he was plagued by other issues as well. Monet wanted to live an aristocratic lifestyle marked by extensive travels, grand homes, and impressive gardens, but his financial reality throughout much of his life prohibited this. Among the cities he was forced to abandon on account of insufficient funds are Paris and the popular haute bourgeoisie resort town of Trouville on the English Channel, both places in which he lived for work but also for the opportunity to interact with the fashionable and wealthy elite.

Figure 4 An entire room in Monet and Chicago is dedicated to several works from Monet’s Haystacks series.

But one’s luck sometimes changes. After the tragic deaths of his first two wives, Monet and his family set down roots in a rented house in the French countryside town of Giverny in 1883, then known for its small but growing arts scene. At just this time, Monet’s Impressionist masterpieces began to gain commercial traction, and Monet was able, after seven years of renting, to purchase his house in Giverny along with its gardens. It was here that, after endless manual and intellectual labor, Monet was able to construct and paint his famous water lily pond and its surrounding gardens. Beginning in the late 1890s and ending in 1926 with his death, Monet painted more than 300 scenes from his garden, including his essential Water Lilies series and the Les Grandes décorations series.

Figure 5 The Tent, Giverny, about 1883-1886.

By the time he died aged 86 in 1926, Monet was both well-known and financially secure, forever altering the course of European art production and American art consumption. Despite his best efforts, Monet became a perennial hit with Americans, who continue to flock to exhibitions of his work with marked excitement, and of these exhibitions, Monet and Chicago is inarguably one of the best. Monet and Chicago is on display at The Art Institute of Chicago until June 14, 2021, with separate exhibition tickets being sold in addition to general admission tickets online at https://www.artic.edu/.

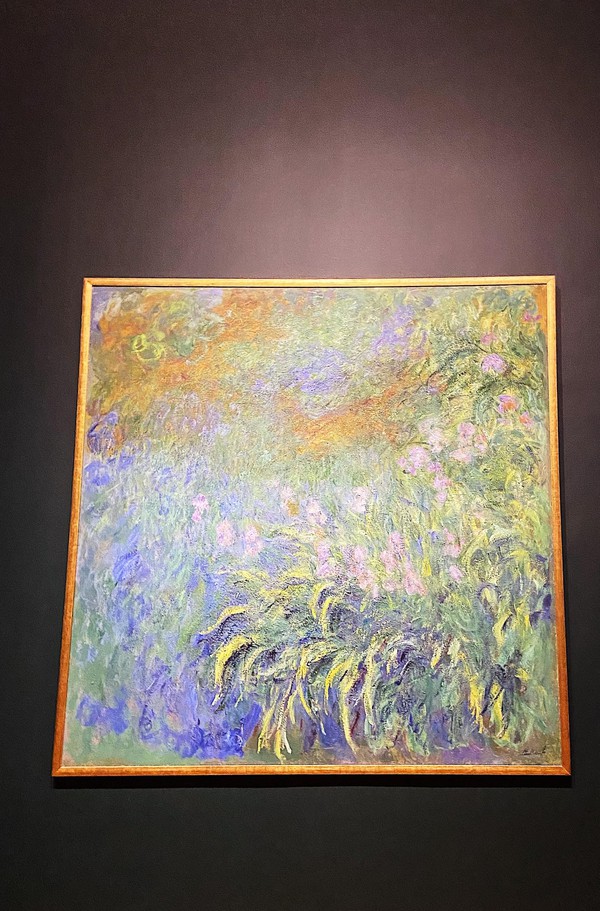

Figure 6 Irises, 1914/1917.