Miles Franklin, August 27th, 2021

In life, we encounter moments in which something that we know intellectually becomes something that we know in a much more personal, even visceral, manner. In many instances, this experience of transforming passive knowledge into that which is known in every fiber of one’s being can be positive, as when one experiences romantic love for the first time. Equally true, however, is the fact that these transformative experiences can occur as a result of a negative experience, the kind of experience which shakes your confidence and can even result in physical illness for a period of time.

For example, until just a few days ago, I knew, intellectually, that jewelry quite often functions as a sort of second skin, a protective barrier between one and the outside world, a barrier which has the additional edge of being beautiful and desirable, but a functional one nonetheless. Of course, as a prolific and avid jewelry wearer, I’ve had moments in which I’ve realized the watchful role my jewelry plays (as when a friend once began psychoanalyzing me over dinner, then began to comment on how much I play with my jewelry when I’m uncomfortable), and I’ve even consciously commented on the matter in a previous interview with MODA Chicago.

(http://www.modachicago.org/blog/2019/10/9/quad-style-miles-harrison?rq=miles%20harrison). My understanding of jewels as protective objects or even as objects which attract good fortune rests on the knowledge that jewelry has, since the beginning of human history, been worn for talismanic and protective purposes, and humans seem to have an intuitive understanding that these practically useless adornments are affixed to boundless metaphysical meanings (for more on this, I direct you to: https://www.nationaljeweler.com/articles/1013-a-look-at-protective-jewelry-through-the-ages). On this point, my colleague Christian Noojin from Sotheby’s Jewels had this to say:

Wearing jewelry to catch the vibe is nothing new. In fact we are repeating the actions of our ancestors. For thousands of years, humans have worn jewelry for protection. Whether for battle or for protection from bad luck, this tradition spans cultures and generations.

If you have studied crystals, you may know that in general, different colors are assigned to different chakras: blue for throat, green for heart, yellow/orange for solar plexus. Wearing a sodalite on the throat may help you communicate calmly and clearly. A malachite on the chest near your heart may soothe emotional woes, and encourage healing. I must express though, there is no right way to wear any particular stone.

A rule of thumb is to wear what feels good. If you are drawn to a green tourmaline necklace that sits right on your throat, it may be a call to speak your heart. If a citrine piece feels right on an earring, your solar plexus may want more influence on your ego.

My tip for people who are beginning their metaphysical journey with jewelry and stones: start with one item. Really learn the energy of the piece, ie. can you feel the vibration of the maker in a handmade piece? Did the previous owner leave their energy in this piece? (Should I sage it?) Do I harness my highest vibrations when I wear this?

From this stage, add on pieces little by little. Before you know it, you will have a whole tool belt of talismans and jewelry for personal growth and maintenance.

The romantic armchair conception of jewels as amulets is a heady thing worthy of one’s Gamay induced contemplation, but this idea became all too real for me in a split second on my recent trip to Florida.

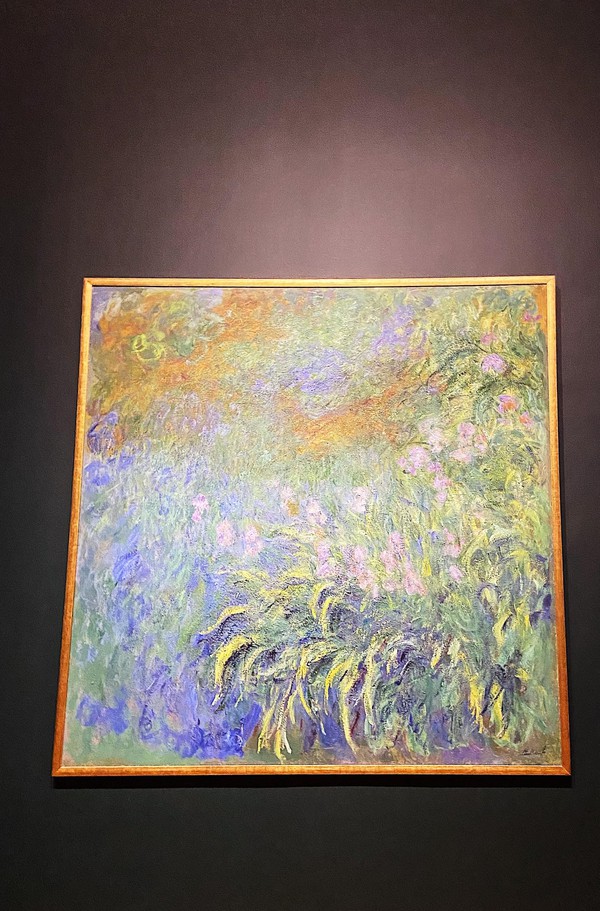

Here, a Van Cleef & Arpels gold and carnelian Vintage Alhambra bracelet, Cartier Love bracelet, and a Cartier gold, mother-of-pearl, and Lapis Lazuli pendant conjure a vision of noble defense and impenetrability.

Each time I make my annual trip to Florida to see my father’s side of the family, I not-so-carefully throw on as much jewelry as is humanly possible because I know that I will need a buffer between me and the homophobic, racist, sexist, and proudly politically incorrect world of the southern United States. Between dinners where sexist sentiments are levied directly at my younger female cousins, the unabashed, simultaneously angry and aroused stares of drunk white homophobic men, and comments from anyone and everyone about the shape, size, and weight of my body, I have boundless occasions to lose my fingers nervously in long necklaces, mountains of bracelets, and fists full of rings.

A Hammerman Brothers diamond bracelet of over 42 carats of diamonds functions as chainmail.

Somehow I was able to avoid direct contact with Florida’s fabulously homophobic hillbillies until I came into contact with one particularly *southern* TSA agent at the Southwest Florida “International” Airport in Fort Myers. As is the case in any airport in the United States, I walked through the metal detector which immediately beeped due to the ridiculous amount of jewelry that I was wearing. Because every other TSA agent at literally every other airport would simply perform a quick, painless pat-down, I was slightly confused when this particular TSA agent (M. Dew, shall we call him) gruffly instructed me to go through the detector again. As anyone with a middle school education might guess, the detector went off, again. After putting me through a third time (just to be really sure, you know), M. Dew told me to step out of line and remove all of my jewelry, making a cupping gesture with his sweaty hands to suggest that he would hold on to my most precious belongings for the moment. Of course, after removing every one of my pieces except for my Cartier Love bracelet, I had to explain to M. Dew and the quickly gathering gaggle of TSA agents that the Love bracelet could not be removed on account of the two screws which fasten it to my wrist. Naturally, M. Dew and crew did not believe me and instead thought that my idea of a good time was to hold up traffic at a regional Florida airport at 5 in the morning, so M. Dew threw in a stern, “well, if you don’t take off the bracelet, I’m gonna have to pat you down…”. “Finally! We’re getting somewhere!” I thought to myself, knowing that, at any other airport in the country, they would have seen the bracelet and started with a pat-down. So, after Dew and Dewier issued their foreboding warning, I told them that I’d be fine with a pat-down. Dew replied loudly and for the benefit of the many Waffle House fueled white men in Bass Pro Shops gear in line behind me, after looking me up and down and up again, “well I wouldn’t be fine with it!”, in a tone and gesture meant to suggest that I wanted to be patted down because of my sexual orientation (and, therefore, my inherent perverted tendencies) and that he would be unwilling to fulfill my burning desire for a 5 a.m. airport pat down from a sweaty Floridian whose underwear surely had more skid marks than either of the airport’s two runways. At this, the gaggle of TSA agents and the aforementioned fish enthusiasts in line began to loudly laugh at me, and I realized that this incident had less to do with airport security and more to do with identifying and humiliating an “other” who so clearly did not look like a single other soul in the airport. Humiliated and feeling naked because my precious jewels were still under the watchful eye of M. Dew, even as he mocked me, I wanted to scream, cry, yell, or maybe just burst into flames. Covering my Love bracelet with my hand as later instructed, I walked through the detector without setting it off, and cautiously picked my beloved objects out of Dew’s surely unwashed hands. My mother tried making light of the situation to me in private, but I found this yet more infuriating because M. Dew’s transgression against me, performed only after the conscious removal of my armor, then and now felt serious and left me with an indelible sense of having been violated. Through this incident, my understanding of my jewels as my protectors moved, with devastating pain, from my brain to my bones, from my seat of knowledge to the very core of my being.

A star sapphire and diamond ring stands sentry against evil intentions.

In the days immediately following my incident in hillbilly hell, I resigned the violated jewels to their respective spots in my jewelry box, completely switching over to pieces that I had not travelled with. I could scarcely even look upon the pieces I’d worn without feeling again, viscerally, the pain, embarrassment, and fear that I’d experienced in the moment of violation. It was only after several long walks in silence and solitude in Princeton following the incident that I was able to arrive at a powerful revelation; the pieces that were stripped from my body by M. Dew should not elicit painful recollections of illiterate TSA agents, because said agents knew that in removing my jewels, they were removing a layer of myself, stripping me down and rendering me all the more assailable. I recall that my intention in wearing so much jewelry to Florida was to offer myself refuge, and it is now clear that this is exactly what my jewels did for me. By both positively and negatively confirming the protective nature of my second skin, I now find myself on the other side of a harrowing incident, a much more confident individual, and one who leans even more heavily into the intangible virtues of jewels.

A Cartier Crash watch (or two) and a personalized stack of jewelry can offer relief in uncomfortable situations.

If you’re looking to begin a purpose-built talismanic jewelry collection, you might start here:

Evil Eye Pendant Necklace — Harwell Godfrey

Jacquie Aiche Onyx Crescent Moon Necklace

Mateo Healing Crystal Necklace

Amulette de Cartier collection – luxury jewelry