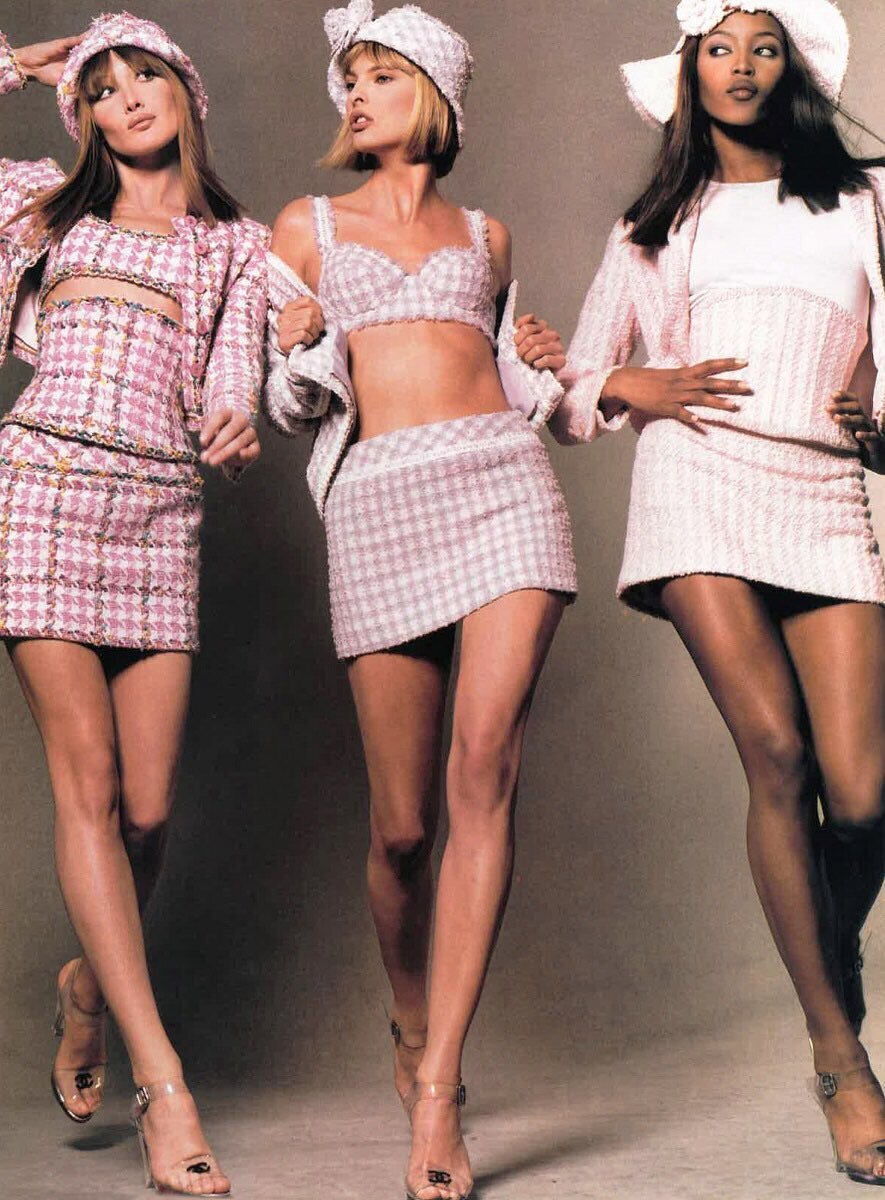

Nostalgia for 1990s and 2000s fashion, with all its attendant glamour and spectacle, seemed to have reached its pinnacle in the summer of 2019, when Instagram models and reality TV stars posted glossy photos wearing Chanel swimsuits and Dior Saddle Bags aboard yachts in the Mediterranean. Despite all of the frivolity and social media flexing that almost overnight turned a 20 year old, $200 derelict Dior bag into a $6,000 piece of vintage art, it was certainly exciting to see so many people introduced to what was arguably the most ambitious and reckless decade of fashion, the 1990s.

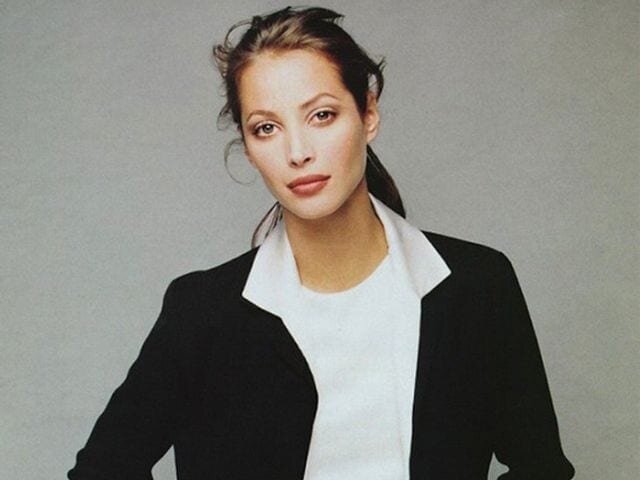

For people interested in diving a bit deeper into the culture of the fashion world during that glorious period, I want to introduce Catwalk, a 1995 documentary direct by Robert Leacock which follows Christy Turlington, Kate Moss, and Naomi Campbell through the three infamously chaotic weeks of fashion shows in Milan, Paris, and New York. In addition to capturing a baffling number of tastemakers in one film, including such legends as Gianni & Donatella Versace, Karl Lagerfeld, Anna Wintour, John Galliano, André Leon Talley, Jean-Paul Gaultier, RuPaul among many others, the documentary also grapples with, and exposes, difficult questions and stereotypes that have long plagued the modeling and fashion industries.

Avoiding superfluous descriptions of the content of the documentary, it is worth noting that the production quality is far above what one might expect from a “day-in-the-life” sort of film; with a gorgeous original soundtrack by none other than pop culture’s darling, Malcolm McLaren, scenes that alternate between black & white and color cinematography, surprisingly disarming monologues, and inherently intimate meetings between models and designers, one is left with both sympathy and reverence for the supermodel.

One particularly endearing moment occurs when an exhausted Turlington arrives back to her hotel room and reflects candidly on the difficulty of maintaining relationships and the lack of rest for months at a time that are inherent in her work. It is in vulnerable moments like this one, shot in black & white, where we see the often overlooked consequences of life as a supermodel, consequences which are overshadowed by the glamorous, fast-paced, and overwhelmingly positive conceptions of this line of work. It is part of the genius of this documentary to uplift these moments of fabulous freedom and allure while also throwing them into relief with moments of much more serious contemplation.

It is yet another part of this documentary’s genius to show the lifelong friendships established between supermodels and the army of people it takes to prepare them for the runway, while simultaneously highlighting the rivalries and dissension within the industry. Turlington is at turns discussing relationship issues and aesthetic affinites with Isaac Mizrahi, and engaging in fruitless career comparisons with other models, making faces at the camera in a manner eerily similar to John Krasinski’s character, Jim, in The Office. Paralleling the polarity of Turlington’s interactions are the scenes showing the models undergoing drastic changes to their appearances for shows which can all too often occur back-to-back and require, for instance, purple hair in the morning and natural hair in the afternoon; it is clear that, in addition taking mental and emotional tolls, modelling at this level takes a physical one as well.

Concerning the topic of appearances, it would be unfair to brush under the rug all of the problematic moments in this documentary, most of which involve issues of appearance and presentation. Two scenes in particular come to mind, the first being a Jean-Paul Gaultier show the premise of which was a very thinly veiled exoticism composed of mock tribal tattoos and facial jewelry on predominantly white models, and the second being a painful scene in which the cinematographer asks André Leon Talley for thoughts concerning John Galliano’s Spring/Summer 1994 show, to which he replies, “a man who respects femininity, and a man who has an appreciation of romance, and a woman who wants to look like a woman.

Of course, he’s not making clothes to go to work, but he’s making clothes for women who want to look like women.” This comment, which flatly states that looking like a women means wearing intricate, heavy couture dresses and also insinuates that acting like a woman entails not working or at the very least dressing like one is not working, was out of place in 1995 and is certainly even more disappointing to hear today, especially from the otherwise brilliant mind of Talley who is himself a champion of diversifying fashion.

The documentary ends with a scene in which an artist paints a minimalistic portrait of Christy Turlington, and the viewer cannot help but feel that they, too, have stared her in the face and distilled a more complete, essential, picture of her and her occupation. Because Catwalk so impartially reveals the beauty and vileness of the world of high fashion and supermodels, all the while doing so with stunning cinematography and a superb soundtrack, I am inclined to recommend it to veterans of vintage fashion as well as fashion fledglings.

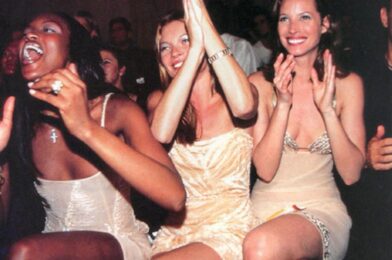

Cover image via — (From left) Naomi Campbell, Kate Moss, and Christy Turlington, 3 elite 90s supermodels who often worked together.